I recently finished a review of E.R. Truitt’s Medieval Robots for Fortean Times. The review should appear in due course, and I don’t want to discuss its content other than that I quite liked the book. However, I thought I would talk about an extract from a medieval source that appears in the book — I mention it in the review but didn’t discuss it in much detail.

Anyway, in the 15th century, Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, paid a shocking amount of money to have the automata at the chateau of Hesdin repaired.

There is a bill for the repairs from 1433 that goes into great detail about what the various automata are, and it’s amazing. Here are some highlights:

Item: for … painting the three figures that squirt water and wet people at well. And at the entrance to the gallery there is a device for soaking ladies when they tread on it; and with it he also made a machine at the entrance to the said gallery; which, when the knobs are touched, strikes those who are underneath in the face and covers them with black or white, and also there is a fountain in that gallery, and which spouts water when one wishes and always when ladies come before it. Item: at the exit of this gallery there is another machine that will strike and cuff all who pass through on their heads and shoulders. Item: in the room before the hermit, a machine makes it rain everywhere … Item: … there is a wooden hermit that speaks to people … And also for paving the place where people go to avoid the showers, where they then fall from on high down onto a sack filled with feathers … a bridge that, at will, makes people who walk on it fall into the water. Item: There are machines in several places, and when one touches the knobs one causes a great quantity of water to fall on people. Item: In the gallery there are six more figures … which soak people in different manners. Item: At the entrance to the gallery [there are] eight pipes for soaking ladies from below and three pipes which, when people stop in front of them, [cause them to be] whitened and covered with flour. Item: there is a window and when people wish to open it a figure in front of it wets people and closes the window on them. Item: there is a lectern with a book of ballards on it and when people try to read it they are all covered with soot … Item: There is a wooden figure that appears above a bench … and it tricks people and can make a cry on behalf of my lord the duke that everybody should go out of the gallery; And those who go because of that cry will be beaten by large figures like idiots …

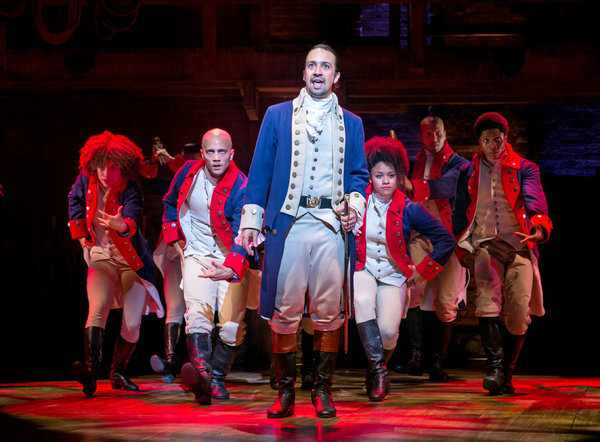

And there’s more of this. I love it. You think about the refined pleasure gardens of the aristocracy, and this guy strolling around them to the accompaniment of lutes:

But actually his lovingly-crafted automata, and please remember that the repairs on these things cost a thousand pounds, which is a lot of money today let alone in 1433, just spray water up ladies’ skirts, dump flour on people and beat them about the face and neck. He’s like the world’s most powerful eight-year-old.