Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle is probably the classic “what if the Nazis won” alternate-history story, which is funny because that isn’t really what it’s about. It’s about reality and illusion, about a bunch of characters engaging in a series of layered pretenses who start to realise that even the “real” world around them is maybe not as real as it might be.

This was always going to be a hard thing to film, but so far, at least, the Amazon adaptation, which I gather has been greenlit for a full series, is doing an OK job.

If you have Lovefilm (or Amazon Prime in the US, or whatever) you can watch it for yourself, so I’m not really going to go into detail about the show itself. Instead, I wanted to take a look at its evocation of an alternate-historical period. The Man in the High Castle poses kind of an interesting problem for adaptation, in that it’s set in an alternate past — that is, it’s an alternative reality, but it’s also set in 1962. So the filmmakers need to portray a world that’s different from our own in two ways — first, it’s fifty years ago, and second it’s not our fifty years ago.

I think that part is done reasonably well. The sets look clunky and lived-in and poor, and you can believe that for people under German or Japanese occupation, times are hard. (Not that plausibility is something you need in an adaptation of a novel where the Nazis drain the Mediterranean to make farmland and are busily colonising space).

But in order to drive home the alternate-reality nature of things, the whole “occupying foreign power” thing is hammered home more than you would expect to see in “reality.” There are swastikas and Japanese flags everywhere. The baddies were swastika armbands with the swastika superimposed on the stripes of an American flag. Newsreels end with “Sieg heil!” There is a swastika on a payphone (OK, a payphone near a border crossing, but still).

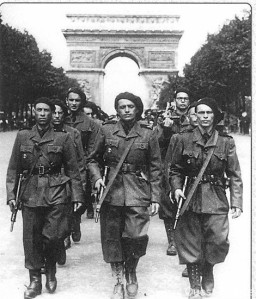

This is not, if I recall correctly, in the book (which I read a really long time ago and do not remember clearly, so I could be wrong). In the book, the eastern part of the US is still the United States, just with a pro-German puppet government in power. And pro-German puppet governments were very much the order of the day. I suppose they tend to get forgotten about because they complicate the narrative? But in any sufficiently large country you can always find some people who are actually pro-Nazi, or who are just trying to make the best of a bad situation, or who want to use the occupiers to further their own agenda, or whatever. France’s “Milice” were, if anything, more despised than the Nazis:

But what you don’t do in that situation is go “Germans Germans Germans, we work for the Germans,” because you need to maintain a skin of plausibility, no matter how thin. OK, you can be a bunch of German stooges, but at least wear berets. Or check these toadying swine out:

Vidkun Quisling, the guy who liked the Germans so much his name became a synonym for treason, but there’s no swastikas on that bad boy. No, it’s all about a heroic, suspiciously-German-looking Norway. If you wanted to run a Nazi-occupied America, the last thing you’d do would be go around painting swastikas on things. You’d want to keep it nice and simple.

But then that wouldn’t be very visual. So by the same logic that turned the novel’s novel into a film in the film, we get a very visually occupied America.

I’m not complaining about that, not at all; the images are very visually striking. I mostly wanted to point out an example of how filmmakers use visual exaggeration to create something that looks plausible or authentic, when the “reality” (if I can use that word here) is probably less “real” looking.

This touches on some of the same issues of cinematic shorthand that bothered me in Kingsman, although in that case specifically that their shorthand for ‘gentleman’ – a man with a posh voice, wearing a bespoke suit and carrying an umbrella – was at odds with its more radical/egalitarian aspirations.

I suppose in some sense you have to be more blunt than in print (say with the Quisling poster) because, unlike that poster, you’re only going to see things in passing in a TV series. Unless you’re pausing a lot.

Yeah, I think there are a lot of problems that level of visual shorthand creates. You get that in a lot of historical films, actually, where things have to be exaggerated lest people miss them.